The Untold Legacy of Adv. T.R. Andhyarjuna: His Pioneering Contribution to Truth-Based Contempt Reform in India

A Jurist’s Intellectual Battle Against Overruled Interpretations in Contempt Law

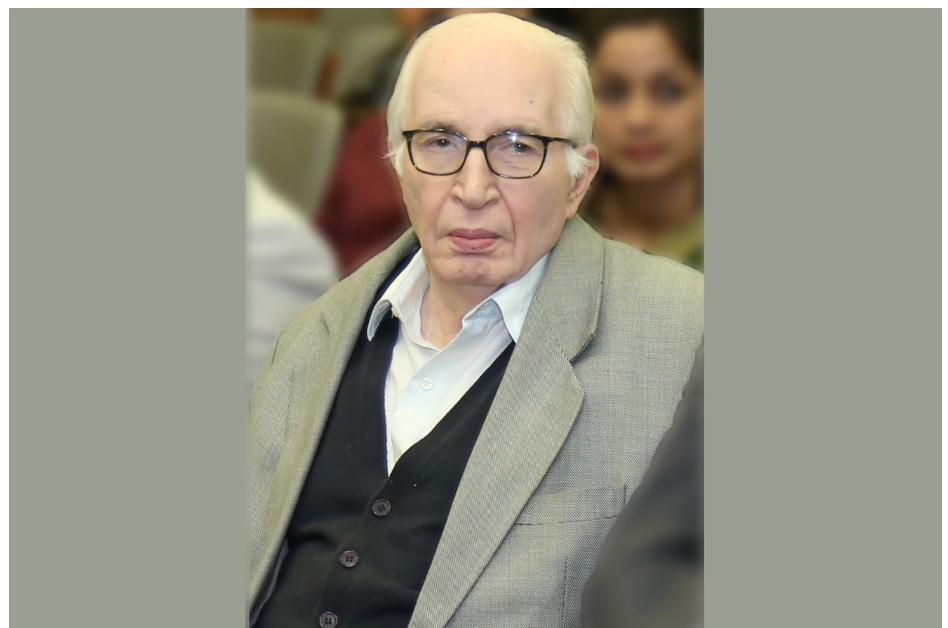

Late Adv. T. R. Andhyarjuna holds a distinguished place in the evolution of Indian contempt jurisprudence, particularly for championing the recognition of “truth” as a legitimate and constitutionally grounded defence. His scholarly interventions—marked by clarity, courage, and doctrinal precision—played a crucial role in correcting the long-standing wrongful application of contempt law based on the non-binding judgment in C.K. Daphtary and the repeated disregard of binding Constitution Bench precedents such as Bathina Ramakrishna Reddy, 1952 SCR 425 (5-J). His work helped dispel misconceptions, resolve doctrinal inconsistencies, and restore constitutional balance in the administration of contempt law.

In his influential article, “Scandalising the Court — Is It Obsolete?”, published in (2003) 4 SCC (Jour) 12, Andhyarjuna meticulously exposed the doctrinal flaws in earlier judicial interpretations, particularly the misplaced reliance on C.K. Daphtary v. O.P. Gupta, (1971) 1 SCC 626. He demonstrated that Daphtary was non-binding and per incuriam, having been rendered in complete disregard of the authoritative Five-Judge Constitution Bench decision in Bathina Ramakrishna Reddy v. State of Madras, 1952 SCR 425. As a matter of law, Bathina—which recognised the centrality of truth, bona fide criticism, and public accountability of judges—remained the controlling precedent under Article 141. Yet this foundational principle was overlooked by several benches and even by members of the Bar, resulting in a series of judgments that mechanically relied on the per incuriam Daphtary ruling.

The Constitution Bench of Five Judges in Bathina Ramakrishna Reddy v. State of Madras, 1952 SCR 425 (5-J), laid down the governing law regarding publication of allegations of corrupt practices by a judge while delivering a judicial order. The Hon’ble Supreme Court ruled as under:

“If the allegations were true, obviously it would be to the benefit of the public to bring these matters into light. But if they were false, they cannot but undermine the confidence of the public in the administration of justice and bring the judiciary into disrepute.”

Andhyarjuna’s scholarly and courageous analysis exposed this judicial dishonesty in unmistakable terms, compelling the legal fraternity to confront long-ignored inconsistencies. His work triggered a renewed and widespread debate across the Bar and academia, prompting jurists, legislators, practitioners, members of the judiciary, and legal commentators to re-examine the constitutional limits of contempt jurisdiction and the dangers inherent in relying on per incuriam precedents. Over time, his views gained substantial traction among members of the Bar, legal scholars, and reform-oriented jurists. This growing recognition contributed significantly to the eventual legislative amendment of Section 13 of the Contempt of Courts Act, which expressly incorporated “truth” as a valid defence in contempt proceedings. The amendment statutorily overruled and effectively neutralised the regressive interpretations exemplified by Daphtary, which had been misused by certain dishonest or incompetent judges to shield misconduct, conceal corruption, and suppress legitimate criticism.

By clarifying the constitutional position and dismantling the intellectual basis of such misused precedents, Andhyarjuna helped reaffirm the enduring principle that the publication of truth exposing corrupt practices of a judge is not an offence, but a constitutional duty undertaken in the larger public interest. Courts derive their moral authority from truth—not from suppressing it. His contribution remains a guiding light in ensuring that the truthful exposure of judicial wrongdoing is recognised not as contempt, but as an act firmly rooted in the public interest.

It has been widely recognised that the most controversial and frequently criticised aspect of contempt jurisprudence is the offence of criminal contempt on the ground of “scandalising the court.” Over the decades, this jurisdiction has often been misused by certain members of the judiciary to silence criticism, deter whistle-blowing, and suppress the exposure of corrupt, biased, or dishonest practices within the judicial system.

Even the Supreme Court, speaking through larger Benches—including in Bar Council of India v. High Court of Kerala, (2004) 6 SCC 311—has candidly acknowledged this problem. In that judgment, the Court approvingly referred to Lord Denning’s famous observation that “no branch of law has been more frequently misused or more widely misinterpreted than the law of contempt”. This recognition reflects a long-standing judicial concern that the offence of “scandalising the court” has too often been invoked not to protect the dignity of justice, but to insulate judicial misconduct from scrutiny.

Constitution Bench decisions in many cases have consistently emphasised that judges, as guardians of citizens’ rights, must exercise contempt jurisdiction with utmost restraint and must refrain from initiating proceedings in doubtful, trivial, or undeserving cases. The power of contempt cannot be used to silence bona fide criticism or to shield judicial shortcomings from public scrutiny. [Baradakanta Mishra v. Registrar of Orissa High Court, (1974) 1 SCC 374, para 91].

Further, in a landmark pronouncement by a Seven-Judge Bench in Powers, Privileges and Immunities of State Legislatures, In re, 1964 SCC OnLine SC 21, the Supreme Court expressly directed all Indian judges to adhere to the classic rule laid down by the Privy Council in Andre Paul Terence Ambard v. Attorney-General of Trinidad and Tobago, 1936 SCC OnLine PC 15. That celebrated decision established a foundational principle: fair, accurate, and truthful criticism of judges or their judgments does not amount to contempt of court. The Court ruled that before holding any person guilty of contempt, it is mandatory to examine whether the impugned statement or publication is true; and where it is based on truth, no conviction can follow.

Moreover, if a person is wrongfully convicted of contempt despite making a truthful statement, he would be entitled to seek compensation from the State, as punishment for truthful disclosure constitutes a violation of fundamental rights under Articles 19 and 21.

However, in C.K. Daphtary v. O.P. Gupta, (1971) 1 SCC 626, the Hon’ble Supreme Court adopted a view directly contrary to the earlier binding precedents, completely overlooking the statutory mandate enacted by Parliament. The judgment laid down an extraordinary and untenable proposition that the statutory provisions governing contempt are not binding upon the Supreme Court, and further held that “truth” or “justification” is not a defence in a case of criminal contempt by way of scandalisation.

The ratio in C.K. Daphtary has been expressly held to be non-binding and stood statutorily overruled by Constitution Bench and larger-Bench authorities. The Hon’ble Supreme Court, in P.N. Duda v. P. Shiv Shanker, (1988) 3 SCC 167, unequivocally ruled in para 39 that C.K. Daphtary does not constitute a binding precedent after the enactment of the Contempt of Courts Act, 1971. This position was reaffirmed in Biman Basu v. Kallol Guha Thakurta, (2010) 8 SCC 673, para 23.

Yet, despite these authoritative pronouncements, certain courts and judges have continued—wrongly and selectively—to rely upon the non-binding and statutorily overridden decision in C.K. Daphtary, thereby perpetuating injustice, violating the statutory mandate, and undermining the settled principles of constitutional and criminal jurisprudence.

In Mamleshwar Prasad v. Kanhaiya Lal, (1975) 2 SCC 232, the Supreme Court unequivocally clarified the doctrine of per incuriam, holding that any judgment rendered in ignorance of an earlier binding ratio is non-binding and does not constitute valid precedent. Similar law is aid down by the constitution benches in the cases of National Insurance Co. Ltd. v. Pranay Sethi, (2017) 16 SCC 680; Vanashakti, 2025 INSC 1326, Official Liquidator v. Dayanand, (2008) 10 SCC 1; and Bajaj Allianz General Insurance Co. Ltd. v. Rambha Devi, (2025) 3 SCC 95.

Despite the specific and statutory overruling, certain judges — including Justice (Retd.) Deepak Gupta — have continued to rely upon the overruled and non-binding decisions in C.K. Daphtary v. O.P. Gupta, (1971) 1 SCC 626, and Pritam Pal v. High Court of M.P., 1993 Supp (1) SCC 529, for the impermissible purpose of suppressing bona fide criticism founded on truth. The conviction of advocates and human rights activists in Re: Vijay Kurle, 2020 SCC OnLine SC 407, by invoking these overruled and non-binding precedents stands as a classic example of judicial power being misused to silence legitimate criticism. The said decision reflects a continued and erroneous reliance on jurisprudence that has been expressly rejected by the Supreme Court itself, thereby undermining constitutional protections, statutory mandates, and the fundamental right to expose corruption and wrongdoing within the judiciary.

It is unfortunate that many advocates lacked a proper understanding of the law and were, therefore, unable to recognize instances of judicial impropriety and intellectual dishonesty on the part of certain judges.

Those who did possess such understanding often refrained from speaking out, fearing judicial displeasure. Some sycophantic senior advocates, including Mr. Milind Sathe and Mr. Kaiwan Kalyaniwalla, went further by promoting and passing resolutions through the Bombay Bar Association (BBA) and the Bombay Incorporated Law Society (BILS) applauding such grossly illegal judgments that were not only per incuriam and unconstitutional but also detrimental to the independence of the Bar.

Amidst this prevailing atmosphere of conformity and judicial silence, the late Shri T.R. Andhyarujina — former Solicitor General of India and one of the most respected constitutional thinkers of our time — emerged as a voice of intellectual clarity and moral courage. Perceiving the deep-rooted inconsistencies and the misuse of contempt jurisdiction, he authored a seminal scholarly article titled “Scandalising the Court — Is It Obsolete?” published in (2003) 4 SCC (Jour) 12.

In this authoritative publication, Shri Andhyarujina undertook a rigorous analysis of the reasoning adopted in C.K. Daphtary v. O.P. Gupta, (1971) 1 SCC 626, and exposed it as a flawed and unsustainable precedent. He forcefully argued that the publication of truth concerning acts of corruption, impropriety, or dishonesty by judges can never amount to contempt of court, thereby reaffirming the constitutional guarantee of free expression and the ethical duty of every advocate to uphold judicial integrity.

His work not only illuminated the doctrinal errors in the Daphtary decision but also catalysed a progressive shift in the jurisprudence of contempt. It has since served as a turning point in the evolution of contempt law, empowering countless citizens, whistle-blowers, and advocates to speak the truth without fear of unlawful retribution. The contribution of Shri T.R. Andhyarujina in restoring balance between judicial accountability and contempt jurisprudence deserves formal and enduring acknowledgment.

In his article “Scandalising the Court — Is It Obsolete?” [(2003) 4 SCC (Jour) 12], the late Adv. T.R. Andhyarujina referenced landmark judgments to support his thesis, such as Bathina Ramakrishna Reddy v. State of Madras, 1952 SCR 425; Bridges v. State of California Times-Mirror Co, 1941 SCC OnLine US SC 144; R. v. Kopyto 47 DLR (4th) 213; and McLeod v. St. Aubyn (1899 AC 549). Drawing upon these authorities, he demonstrated that the publication of truthful information especially in exposing corruption or dishonesty among judges is not contempt, and that legal standards must balance protection of judicial integrity with the right to legitimate criticism grounded in truth.

Following the publication of Shri T.R. Andhyarujina’s landmark article, the National Commission to Review the Working of the Constitution (NCRWC) — comprising eminent jurists and senior advocates including Shri Shanti Bhushan and Shri Ram Jethmalani — undertook a comprehensive evaluation of the misuse of contempt powers, particularly the flawed reasoning in C.K. Daphtary v. O.P. Gupta, (1971) 1 SCC 626. The Commission categorically acknowledged the doctrinal defects in the Daphtary precedent and strongly advocated for a statutory reform to protect truthful criticism of the judiciary.

The NCRWC formally recommended that the contempt law be amended to recognise “truth” as a complete defence, emphasising that public accountability, transparency, and the independence of the legal profession demand that bona fide exposure of judicial misconduct must never be penalised.

- Download the report of National Commission to Review the Working of the Constitution (NCRWC):-

Download the article by shri T.R. Andhyarujina on SCC which is reported as “Scandalising the Court — Is It Obsolete? (2003) 4 SCC (Jour) 12”.

Link: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1vsf_BEyVWWOnqzzE357X8yB70apOtCiT

The NCRWC report also relied upon the views of renowned constitutional scholar H.M. Seervai, who unequivocally opined that C.K. Daphtary was bad law and ought not to be followed. It was in view of these expert assessments — and the clear consensus emerging among constitutional jurists, senior members of the bar, and human rights advocates — that the Parliament, in 2006, amended the Contempt of Courts Act, 1971. By inserting Section 13(b), Parliament expressly provided that “truth” shall be a valid defence in contempt proceedings, thereby restoring the balance between judicial dignity, constitutional accountability, and the freedom to expose corruption within the judiciary.

Since the 2006 legislative amendment, the Hon’ble Supreme Court has delivered several landmark judgments that have strengthened the statutory defence of truth in contempt cases while curbing discretionary abuse. These rulings have played a critical role in reinforcing judicial accountability and preventing the misuse of contempt powers, thereby aligning the law with the constitutional values of transparency, democratic scrutiny, and public interest.

The key judgments include:

(i) Subramanian Swamy v. Arun Shourie, (2014) 12 SCC 344 (5-J) which uphold the ratio in Indirect Tax Practitioners’ Assn. v. R.K. Jain, (2010) 8 SCC 281;

(ii) Re: C.S. Karnan, (2017) 7 SCC 1, which upheld Re: Lalit Kalita, (2008) 1 Gau LT 800.

In Subramanian Swamy v. Arun Shourie, (2014) 12 SCC 344, the Hon’ble Supreme Court ruled as under:

“12. In Wills [Nationwide News (Pty) Ltd. v. Wills, (1992) 177 CLR 1 (Aust)], the High Court of Australia suggested that truth could be a defence if the comment was also for the public benefit. It said, ‘… The revelation of truth—at all events when its revelation is for the public benefit—and the making of a fair criticism based on fact do not amount to a contempt of court though the truth revealed or the criticism made is such as to deprive the court or Judge of public confidence…’.”

This authoritative articulation confirms that truth, when revealed, can never constitute contempt of court—even if it exposes judicial misconduct or results in diminished public confidence in a particular judge. The law further mandates that courts must not take cognizance of contempt unless it is prima facie clear that the allegations are false; in the absence of such clarity, initiation of contempt proceedings is impermissible.

In Indirect Tax Practitioners’ Assn. v. R.K. Jain, (2010) 8 SCC 281, the Hon’ble Supreme Court authoritatively clarified the meaning and scope of “scandalous pleadings.” The Court held that when a judge is alleged to have committed fraud, corruption, misconduct, or any act amounting to abuse of judicial office, a person who files a complaint or makes pleadings attributing motive, corruption, or fraud against the judge is not guilty of contempt. It was expressly ruled that allegations of this nature—when forming part of a bona fide complaint process or judicial proceeding—cannot be treated as “scandalisation of the court”; rather, they are essential for ventilating genuine grievances against dishonest or corrupt judges.

The Supreme Court emphasised that truthful allegations exposing corruption or fraud by a judge, when made through proper legal channels, are constitutionally protected and do not amount to contempt, since such disclosures are indispensable to maintaining integrity, transparency, and accountability within the judiciary. This judgment reaffirmed that the dignity of the judiciary is strengthened—not diminished—when genuine complaints of judicial misconduct are brought to light. The nation must acknowledge the pivotal role of Senior Advocate Shanti Bhushan, who argued this historic case, and the profound contribution of Hon’ble Justices G.S. Singhvi and Asok Kumar Ganguly, who authored this landmark judgment. Their combined efforts reshaped and humanised the doctrine of criminal contempt in India, ensuring that the shield of contempt law is never misused to silence truth, suppress legitimate criticism, or protect corrupt judicial officers.

These Hon’ble Judges unequivocally laid down the historic proposition that exposing corrupt judges is not merely permissible, but constitutes a constitutional duty under Article 51A of the Constitution of India, which enjoins every citizen to uphold truth, integrity, and the highest standards of public morality. This principle affirms that safeguarding the purity of the justice system is a shared responsibility of all citizens, and that truth spoken in public interest can never amount to contempt..

Law is also settled that, if a particular judge or magistrate is corrupt and sells justice, then making a bona fide complaint to the higher authorities seeking action against such a delinquent judicial officer is itself an act aimed at preserving the purity of the administration of justice. It would be unthinkable that a judicial officer should be allowed to take bribes with impunity, and that any citizen who brings this misconduct to the notice of the appropriate authorities should be hauled up for contempt of court. [Rama Surat Singh Vs. Shiv Kumar Pandey 1969 SCC OnLine All 226, KaziRam Piarra comrade 1972 SCC OnLine P&H 277, Baradkanta Mishra (1974) 1 SCC 374 ]

Three Judge Bench in S.R. Ramraj Vs. Special Court,Bomay AIR 2003 SC 3039: (2003) 7 SCC 175, ruled as under;

“(A)Contempt of Courts Act (70 of 1971), S.2- Contempt – Pleading/defense made on basis of facts which are not false – Howsoever the pleading may be an abuse of process of Court – Does not amount to contempt – Merely because an action or defence can be an abuse of process of the Court those responsible for its formulation cannot be regarded as committing contempt – The entire proceedings in relation to contempt of Court shall stand set aside. (Para 9)

We, therefore, set aside the order made by the learned Judge of the Special Court initiating the proceedings for contempt and convicting the appellant for the same. The entire proceedings in relation to contempt of Court shall stand set aside. The appeal is allowed accordingly.”

In view of the law laid down by the Hon’ble Supreme Court, including Larger Constitution Benches, in the cases of Indirect Tax Practitioners’ Association v. R.K. Jain, (2010) 8 SCC 281; Subramanian Swamy v. Arun Shourie, (2014) 12 SCC 344; S.R. Ramraj v. Special Court, Bombay, (2003) 7 SCC 175; Bathina Ramakrishna Reddy v. State of Madras, AIR 1952 SC 149; Amicus Curiae v. Prashant Bhushan, 2022 SCC OnLine SC 1188; State of Maharashtra v. Mangesh, 2020 SCC OnLine Bom 672; and Lalit Kalita, In re, (2008) 1 Gau LT 800, the settled legal position is summarized as under:-

Whenever a Judge commits serious criminal offences, including acts of corruption or conduct which undermines the dignity of the Court, it is in the paramount public interest that such misconduct is exposed. In such circumstances, every citizen is not merely entitled, but is in fact duty-bound under Article 51-A of the Constitution of India to bring such misconduct to the knowledge of the public and to lodge appropriate complaints before the competent authorities. The underlying rationale is clear: society cannot permit criminals occupying judicial office to escape accountability, for inaction in the face of such grave impropriety breeds “social pollution”, pollutes the pure fountain of justice and inevitably erodes the confidence of the common man in the justice delivery system. It is a settled proposition of law that the truthful publication of judicial or judicial-related misconduct does not constitute contempt of court, even if such publication and criticism may tend to diminish public confidence in the said individual Judge(s) or in the Court itself. The right of citizens to demand a clean, incorruptible, and untainted judiciary is an integral component of the constitutional guarantee of the rule of law, and this right cannot be curtailed, diluted, or silenced by resorting to the extraordinary jurisdiction of contempt.

And in a situation where the defendants in contempt proceedings place material pleadings or make submissions founded upon truth, such pleadings cannot be branded as scandalous or contemptuous—even if they are unpalatable, appear critical of the institution, or are alleged to be an abuse of the process of the Court. So long as the statements are based on truth and raised in defence, they are not only permissible in law but are also constitutionally protected expressions. The judiciary must not be oversensitive to criticism. On the contrary, bona fide and constructive criticism of judicial conduct and functioning is to be welcomed, for it opens the doors to self-introspection, improvement, and public confidence. Judges, like all human beings, are not infallible; they may err, albeit inadvertently, owing to individual perceptions or limitations. It is in this spirit that the Hon’ble Supreme Court has repeatedly observed that the shield of contempt jurisdiction cannot be used to stifle legitimate discussion, truthful disclosure, or fair criticism. The dignity of the institution is preserved not by suppressing criticism, but by demonstrating that it can withstand scrutiny and correct itself when required.

It is a settled principle of law that when a judge or magistrate is alleged to be corrupt or engaged in the “sale of justice,” a bona fide complaint addressed to higher authorities seeking action against such a delinquent judicial officer does not constitute contempt of court. On the contrary, such action is undertaken to preserve and protect the purity of the administration of justice.

The law firmly recognizes that it would be unthinkable, irrational, and contrary to public policy to permit a judicial officer to accept bribes or misuse judicial power, while simultaneously prosecuting a citizen who brings such grave misconduct to the attention of competent authorities. Reporting judicial corruption through proper and lawful channels is a legitimate grievance mechanism, fully consonant with constitutional morality and the integrity of judicial institutions.

Thus, bona fide allegations of judicial corruption or misconduct, fall entirely outside the scope of contempt jurisdiction. Rather than undermining the judiciary, such disclosures strengthen judicial accountability and uphold the foundational principles of transparency, fairness, and rule of law. [ Rama Surat Singh Vs. Shiv Kumar Pandey 1969 SCC OnLine All 226, Ram Piarra comrade 1972 SCC OnLine P&H 277, Baradkanta Mishra (1974) 1 SCC 374]

Despite these clear statutory and judicial pronouncements rejecting the validity of C.K. Daphtary, certain judges — most notably Justice (Retd.) Deepak Gupta, who has been widely criticised as “Mr. Overruled” — continued to rely on the overruled decisions of C.K. Daphtary, Pritam Pal and D.C. Saxena (Dr) v. Hon’ble The Chief Justice of India, (1996) 5 SCC 216, to convict advocates for contempt. This judicial impropriety was prominently manifested in In Re: Vijay Kurle, (2021) 13 SCC 616, where convictions were recorded by relying on precedents that had been expressly discarded by statute and subsequent Supreme Court judgments.

This same flawed and unconstitutional reasoning was later invoked in the conviction of Advocate Prashant Bhushan in In Re: (Contempt Matter), (2021) 3 SCC 160 — a decision similarly challenged for relying on disapproved and overruled jurisprudence.

Renowned Senior Advocate and author Shri Aseem Pandya exposed the inherent illegality, doctrinal defects, and constitutional infirmities in both In Re: Vijay Kurle, (2020) SCC OnLine SC 407 [(2021) 13 SCC 616], and In Re: Prashant Bhushan, (2021) 3 SCC 160, through a detailed article titled “Arrogation of Unlimited Contempt Power by the Supreme Court: A Hornet’s Nest Stirred Up Again” published on LiveLaw on 16.09.2020.

Both the above judgments are presently under challenge before larger Benches of the Supreme Court. Writ petitions have already been admitted in Prashant Bhushan v. Union of India, 2022 SCC OnLine SC 2222, and the matters are likely to be listed shortly before a Bench headed by Hon’ble Justice M.M. Sundresh.

Adv. Ishwarlal Agarwal

Chairman, Supreme Court Lawyers Association