The order of the Chief Justice of the Bombay High Court, Shri Chandrashekhar, reminded citizens and advocates of the historic principle that even judges — including those of the Supreme Court — and government officials can be held personally liable to pay compensation for wrongful or arbitrary orders. The reference to “McLeod v. St. Aubyn (1899 AC 549)” has thus become a landmark precedent.

In this case, the Acting Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Sir St. Aubyn, who had authored the erroneous contempt judgment, was himself impleaded as a party-respondent and was directed to personally pay compensation to the advocate who had been wrongfully convicted. This judgment is of great help to 15 advocates who recently filed the Writ Petition seeking compensation.

The National President of the Indian Bar Association, Adv. Nilesh Ojha, along with the Chairman of the Supreme Court Lawyers Association, Adv. Ishwarlal Agarwal, and its Vice-Chairman, Adv. Vijay Kurle, Woman Wings Adv. Nicky Poker expressed their profound gratitude to Chief Justice Chandrashekhar for enlightening the legal fraternity and advocates across the nation about this landmark judgment.

Recently, fifteen advocates, including women lawyers, have filed a writ petition seeking compensation of ₹50 lakhs each. The aforesaid landmark judgments—reaffirmed and relied upon by the Five-Judge Bench—hold great significance and are likely to substantially aid the petitioners in securing the compensation sought for the violation of their fundamental rights.

Mumbai:

In a significant and thought-provoking development, the recent order dated 17th September 2025 passed by a Five-Judge Bench headed by Learned Chief Justice Shri Chandrashekhar, along with Justices M.S. Sonak, Ravindra Ghuge, A.S. Gadkari, and B.P. Colabawalla, has unexpectedly turned into a blessing in disguise for the legal fraternity and common citizens alike.

While deciding a contempt matter, the Bench referred to two landmark judgments of the Privy Council, namely:

1. McLeod v. St. Aubyn (1899 AC 549); and

2. Ambard v. Attorney General of Trinidad and Tobago (1936 AC 322).

These two decisions laid the foundation for a globally recognized principle of judicial accountability, establishing that when a Chief Justice of Supreme Court or any Judge passes a wrongful order of contempt, causing loss or suffering to a citizen or an advocate, such Judge can be made personally liable to pay compensation.

The McLeod v. St. Aubyn (1899 AC 549) Precedent

In McLeod v. St. Aubyn, the Privy Council set aside a contempt conviction passed by the Supreme Court of Jamaica.

The Acting Chief Justice, Sir St. Aubyn, who had authored the erroneous judgment, was himself impleaded as a party-respondent and was directed to pay compensation to the wrongfully convicted advocate.

This landmark precedent unequivocally establishes that even the Chief Justice of the highest court is not immune from personal liability when his judicial acts result in demonstrable harm to a citizen, advocate, or litigant by reason of illegality, arbitrariness, or mala fide exercise of judicial power.

The Kerala High Court in Mohd. Nazer M.P. v. State , 2022 SCC OnLine Ker 7434, directed an inquiry under Section 340 CrPC against a Judge accused of fabricating judicial records, even ordering his suspension—affirming that judicial officers are not above the law.

In S.P. Gupta v. Union of India, AIR 1982 SC 149, the Chief Justice of India himself was made a party respondent and represented through private counsel, reaffirming that even constitutional judges are accountable under law.

The Ambard v. Attorney General Principle

In Ambard v. Attorney General (1936 AC 322), the Privy Council strongly criticized the Supreme Court of Trinidad for wrongfully convicting a newspaper editor who had published truthful comments on inconsistent and arbitrary judicial orders passed by a High Court Judge.

The Privy Council held that when the Court itself could not declare the publication to be untrue, convicting the editor amounted to gross injustice and a clear misapplication of the contempt jurisdiction. It observed that the Supreme Court had misconceived the very scope and object of contempt powers, using them to shield judicial errors from public scrutiny rather than to uphold the dignity of justice.

Consequently, the Privy Council set aside the conviction, declared the proceedings to be a misuse of contempt jurisdiction, and directed the Attorney General to pay the costs incurred by the editor before all courts.

This historic ruling reaffirmed that truthful criticism of judicial actions does not constitute contempt, and that judges, like all public functionaries, must remain accountable to the public through reasoned transparency and lawful restraint.

In Re S. Mulgaokar, Justice VR Krishna Iyer observed:

“To criticise the judgment fairly, albeit fiercely, is no crime but a necessary right, twice blessed in a democracy….Where freedom of expression, fairly exercised, subserves public interest in reasonable measure, public justice cannot gag it or manacle it, constitutionally speaking. A free people are the ultimate guarantors of fearless justice.”

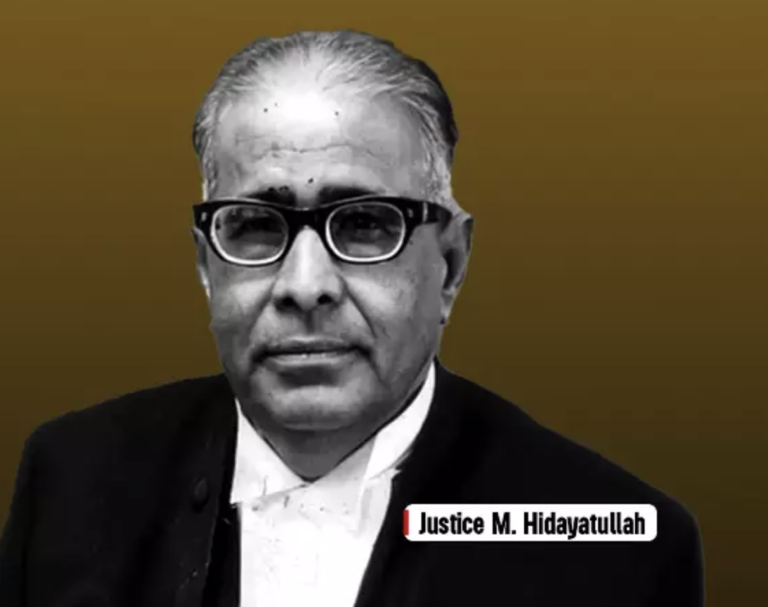

Chief Justice Hidayatullah let him off with a caution, saying:

“The court, like any other institution, does not enjoy immunity from fair criticism. This court does not claim to be always right …. They do not think themselves in possession of all truth or hold that wherever others differ from them, it is so far error. We are constrained to say also that fair and temperate criticism of this court or any other court even if strong, may not be actionable….”

Recently, fifteen advocates have filed a writ petition seeking compensation of ₹50 lakhs each, and the aforesaid judgments—reaffirmed and relied upon by the Five-Judge Bench—are highly significant and beneficial for these petitioners in securing the relief of compensation claimed.

Law in India on Compensation from the State for Wrong Orders of Courts Resulting in Violation of Fundamental Rights

The principle of personal and state accountability for wrongful judicial acts has also been recognized by Indian courts and international bodies.

1. In Ramesh Lawrence Maharaj v. Attorney General of Trinidad & Tobago (1978) 2 WLR 902, the Privy Council granted compensation to an advocate who was unlawfully convicted of contempt by a High Court Judge. It was ruled that since the Judge acts as part of the State’s executive arm, the State is vicariously liable to compensate the victim.

2. This doctrine has been affirmed by the Supreme Court of India in:

o D.K. Basu v. State of West Bengal, (1997) 1 SCC 416;

o Nilabati Behera v. State of Orissa, (1993) 2 SCC 746;

o People’s Union for Civil Liberties v. Union of India, (1997) 3 SCC 433;

These cases hold that when a citizen’s fundamental rights are violated by unlawful or mala fide judicial or executive action, the State must compensate the victim and recover the amount from the delinquent officials.

Reinforcement from International Forums

A 17-Judge Bench of the United Nations Human Rights Committee, including Justice P.N. Bhagwati, in Anthony Michael Emmanuel Fernando v. Sri Lanka (2005 SCC OnLine HRC 22), condemned the Chief Justice of Sri Lanka for an arbitrary contempt conviction and held it violative of Article 9 of the ICCPR, directing the State to compensate the victim and to establish appellate safeguards even against contempt orders passed by Supreme Courts.

Indian jurisprudence has consistently evolved to provide monetary redress for judicial and administrative wrongs:

· Walmik Bobde v. State of Maharashtra, 2001 ALL MR (Cri) 1731; and

· Bharat Devdan Salvi v. State of Maharashtra, 2016 SCC OnLine Bom 42 —

both recognized the State’s duty to compensate citizens for rights violations caused by wrongful judicial orders.

Further, the Supreme Court in Directions in the Matter of Demolition of Structures, In re, (2025) 5 SCC 1, speaking through CJI Bhushan Gavai, observed:

“Respect for the rights of individuals is the true bastion of democracy. The State must repair the damage done by its officers to the petitioner’s rights. It may have recourse against those officers.”

Likewise, in Lucknow Development Authority v. M.K. Gupta, AIR 1994 SC 787, the Court ruled that:

Reaction from Legal Fraternity

Adv. Nilesh Ojha, National President of the Indian Bar Association,

Adv. Ishwarlal Agarwal, Chairman of the Supreme Court Lawyers Association, and Adv. Vijay Kurle, Vice-Chairman, expressed gratitude to Chief Justice Chandrashekhar for citing these historic Privy Council decisions.

They stated that by doing so, the Hon’ble Chief Justice has enlightened thousands of advocates about a forgotten but powerful legal principle — that even the highest judicial authorities can be held accountable and that citizens wronged by judicial excesses have a constitutional right to seek compensation.