Chief Justice of India Surya Kant has now emerged as one of the most reform-driven CJIs in Supreme Court history — by boldly proposing a National Judicial Policy aimed at eliminating divergence in judicial outcomes across Supreme Court benches and the twenty-five High Courts of India.

Through this stand, he has struck directly at the long-standing structural imbalance that prevents the common citizen and the young advocate from receiving real, equal and predictable justice.

This judicial direction is fully aligned with the Supreme Court’s evolving jurisprudence on judicial discipline and accountability. In Ratilal Jhaverbhai Parmar v. State of Gujarat, 2024 SCC OnLine SC 298, Rohan Vijay Nahar v. State, 2025 SCC OnLine SC 2366, and Vanashakti v. Union of India, 2025 INSC 1326, the Supreme Court has made its position unmistakably clear — co-ordinate benches cannot deliver conflicting or divergent views and are bound to follow precedent laid down by larger or co-equal benches. Any judgment rendered by ignoring the ratio laid down by a larger or co-equal Bench is per incuriam, non-binding in law, lacks precedential value, and liable to be set aside on this ground alone. Further, a Judge who consciously ignores, bypasses, or refuses to apply binding precedent breaches judicial discipline and violates the oath of constitutional office.

This principle is fortified by Pradip J. Mehta v. CIT, (2008) 14 SCC 283, wherein the Supreme Court held that High Courts cannot depart from the views of other High Courts without recording compelling legal reasons. Judicial consistency is therefore not optional — it is a constitutional mandate.

It is also now clearly declared by the Supreme Court that selective application of law is not a mere judicial error — it is misconduct, a wilful departure from constitutional duty. A judge who breaches the judicial oath becomes unfit to continue in office, and it is a misbehaviour, attracting constitutional consequences including removal under Articles 124/217 read with the Judges (Inquiry) Act.

Further, such conduct of Judges in not following binding precedents is not only unconstitutional but also penal in nature, and is punishable under Sections 2(b), 12 and 16 of the Contempt of Courts Act, 1971, as well as Sections 198 and 257 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS). These legal provisions collectively deliver one unmistakable message — the era of judicial unaccountability cannot and will not survive; the law now stands firmly with the citizen and the Constitution, not with power, immunity, or institutional entitlement.

That the U.S. Supreme Court in Scheuer v. Rhodes, 416 U.S. 232, 94 S. Ct. 1683, 1687 (1974), articulated a principle of constitutional accountability which continues to hold global relevance. The Court ruled:

“When a State officer acts under State authority in a manner violative of the Federal Constitution, he comes into conflict with a superior Constitutional mandate. In such circumstances, he is stripped of his official character and is answerable in his personal capacity for the consequences of his unlawful acts. The State cannot grant immunity to shield him from accountability to the supreme authority of the Constitution. A Judge, being a State officer, when acting in violation of Constitutional rights, acts not as a Judge, but as a private individual.”

This landmark pronouncement confirms an uncompromising position: no office, title or judicial robe can immunise unconstitutional acts. If a Judge exceeds legal authority, abuses power, or violates fundamental rights, he does not act as a Judge, but as a private person — and therefore attracts personal civil, criminal and constitutional liability. Judicial power is not armour; the moment it departs from law, judicial protection falls away, accountability begins.

This principled stand has been warmly welcomed by the Indian Bar Association, which observed that CJI Surya Kant has, like an expert physician, diagnosed the core ailment of the judicial system and also prescribed the correct cure. The Association stated that his approach strengthens the framework of judicial certainty, restores institutional accountability, and aligns the justice system back to constitutional discipline.

According to Adv. Nilesh Ojha, National President of the Indian Bar Association, this reform-driven judicial shift will drastically reduce unpredictability in judgments, restrict misuse of discretion, and curb injustices stemming from judicial arrogance, bias, or corruption.

He emphasised that judicial power must always function within the framework of law — never above it. The Association further emphasised that uniform adherence to precedent rebuilds public trust, ensures that no litigant has to gamble between courts for different outcomes, and guarantees that justice flows from reasoned law rather than power, influence or personality. When binding precedent is followed in its true form, the common citizen receives certainty instead of confusion — and the rule of law stands taller than individual discretion.

In a landmark articulation, the CJI issued a historic and categorical reminder to all Constitutional Courts — that conflicting rulings between High Courts, or even between coordinate benches of the Supreme Court, are impermissible and must come to an end. Judicial discipline, he clarified, is not negotiable.

Justice Surya Kant’s message is thus not new — it is the authoritative consolidation of decades of precedent, now delivered with a clarity the system can no longer afford to overlook.

This intervention by the CJI marks a decisive shift toward a more accountable and disciplined judiciary, and the Bar considers it a step capable of restoring public confidence in the justice system.

This warning is guided by the judicial precedents laid down by the Supreme Court constitution benches and recently reaffirmed by the larger bench in

Chief Justice of India Surya Kant, speaking on Constitution Day, delivered a powerful message — that predictability in judicial reasoning must be restored across all courts in the country, and that the divergence arising from twenty-five High Courts and multiple Supreme Court benches must be decisively reduced.

“It is high time we minimise unpredictability and avoidable divergence that may arise simply because there are twenty-five High Courts or multiple benches of the Supreme Court,” he said. “Justice cannot be like instruments playing harmonious notes in isolation but discordant sounds when heard together. We must strive for a judicial symphony — one rhythm, expressed in many voices and languages, yet guided by a common constitutional score.”

Addressing the gathering at the Supreme Court’s Constitution Day function, the CJI proposed a landmark conceptual reform — the formulation of a uniform national judicial policy to ensure coherence and doctrinal consistency across jurisdictions.

“A uniform, national judicial policy — an institutional framework that encourages coherence — can help our courts speak with clarity and consistency,” he observed.

Access to Justice Must Not Be Theoretical — It Must Be Real

CJI Surya Kant stressed that access to justice remains out of reach for many, despite constitutional proclamations. He warned that rights become ornamental when the remedies to enforce them are inaccessible, and constitutional guarantees lose meaning for ordinary citizens.

He further highlighted that Articles 32 and 39-A make access to justice explicit and indispensable, placing the responsibility of protection squarely on the Supreme Court and High Courts:

“Our framers knew that a Constitution which proclaims rights without providing means to enforce them is not a true testament of justice.”

The CJI noted a clear gap between the Constitution’s promise and the lived reality of citizens who face financial, linguistic, geographical and procedural barriers.

“If access to justice is our moral and constitutional North Star, then predictability, affordability and timeliness form its core supports.”

The CJI said there is still a gap between the constitutional vision and the experience of many people who face barriers of cost, language, distance and delay.

“If access to justice is our moral and constitutional North Star, then predictability, affordability, and timeliness form its core supports. Despite that, when we look closely at the functioning of our Justice Delivery System, there is still a disquieting gap between this constitutional vision and the experiences of many – particularly those on the margins – for whom the ideal of access to justice remains elusive due to exorbitant cost, language, distance, and delay. These barriers weaken the very overarching goal we seek to protect and, in doing so, magnify existing inequalities”,

He concluded by stating that the strength of a constitutional democracy lies not in the proclamation of rights but in the capacity to secure them.

“Let us continue the work of building a justice system that resonates with every individual who seeks its protection and remains faithful to the principles enshrined in our Constitution. Let us reaffirm that the strength of a constitutional democracy lies not merely in its proclamation of rights, but in its steadfast capacity to secure them”, he concluded.

In the recent judgment of Vanashakti, 2025 INSC 1326, where a three-Judge Bench set aside a two-Judge Bench ruling that had ignored earlier co-equal Bench decisions. The Court reiterated the doctrine laid down in:

- Official Liquidator v. Dayanand, (2008) 10 SCC 1; and

- Bajaj Allianz General Insurance Co. Ltd. v. Rambha Devi, (2025) 3 SCC 95

that the tendency of some Judges to avoid binding precedents by pointing out minor or trivial factual distinctions is wholly impermissible. Such conduct reflects disrespect to the constitutional ethos and constitutes a serious breach of judicial discipline.

A warning on credibility and chance litigation

The Court observed that deviations of this kind:

- seriously undermine the credibility of the judicial institution,

- disrupt the uniform development of law, and

- promote chance litigation—directly harming the rule of law.

The Bench noted that predictability and certainty are the hallmarks of Indian judicial jurisprudence evolved over the last six decades. Conflicting judgments of superior courts cause incalculable harm, generating uncertainty and confusion among litigants, lawyers, and authorities alike.

In Ratilal Jhaverbhai Parmar v. State of Gujarat, 2024 SCC OnLine SC 298,

the Supreme Court of India delivered an unequivocal ruling with far-reaching impact: A judge who neglects, omits, or wilfully refuses to apply the law and binding ratio declared by the Supreme Court betrays the trust of the nation.

The Court held that such conduct amounts to a breach of judicial oath, because deliberate disregard of binding precedent is not a mere legal error — it is a direct assault on judicial discipline and a serious disservice to litigants and to the institution of justice itself. It was also held that such Judges are bringing disrepute to the entire institution.

The Supreme Court further underscored that judicial power is not a personal privilege, but a constitutional trust, and must be exercised strictly within the mandate of:

📌 Article 141 — Law declared by the Supreme Court is binding on all courts in India.

📌 Article 144 — All authorities, including the judiciary, must act in aid of the Supreme Court.

Thus, any deviation from binding precedent is a constitutional wrong, striking at the core of judicial accountability.

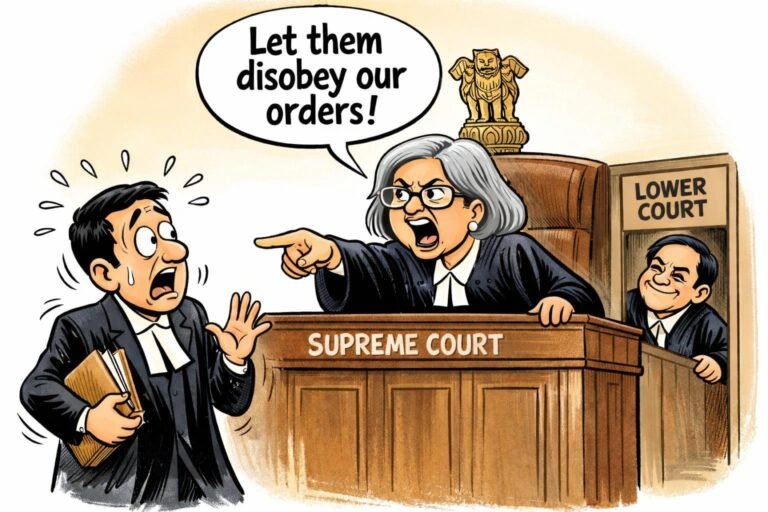

It has been a longstanding grievance among litigants, lawyers and even jurists that certain corrupt or compromised judges habitually disregard the binding law declared by the Supreme Court, and continue to pass orders in open violation of precedent. This pattern often manifests in two ways:

By completely ignoring binding Supreme Court judgments, as though no such law existed, or By referring to the precedent only to distort, twist or selectively extract portions, while refusing to apply the actual ratio — often without even recording what the true binding principle is.

Such conduct does not constitute a mere judicial error — it reflects a wilful breach of judicial oath, and is today being recognised as judicial dishonesty and abuse of authority.

For the first time, the Supreme Court has explicitly captured, condemned and criminalised this pattern of misconduct. The recent rulings in Ratilal Jhaverbhai Parmar and Rohan Vijay Nahar mark a turning point in Indian judicial accountability, ensuring that no judge — regardless of rank or influence — can escape responsibility for violating Article 141.

These judgments are not merely legal pronouncements; they are the trigger point for a coming judicial revolution.

They will empower litigants, expose fraudulent judicial practices, strengthen constitutional discipline in courts across the country, and restore public faith in the justice system.

CONSTITUTIONAL RESPONSIBILITY OF JUDGES:- The judgment underscores that those entrusted with administering the judicial system—and who take an oath to uphold the Constitution—must exemplify the highest commitment to constitutional principles and judicial discipline. This burden is especially weighty for Judges, who wield the power to decide critical constitutional and legal issues and who serve as guardians of individual and societal rights.

A constitutional reminder from the Supreme Court

“Discipline is the sine qua non for the effective and efficient functioning of the judicial system. If Courts command others to follow the Constitution and the rule of law, they cannot themselves violate constitutional discipline.”

It is further ruled that Judges owe an institutional duty to uphold the certainty, stability, and predictability of law. Judicial decisions must therefore be anchored in established legal principles, and courts are expected to justify their conclusions by applying the settled doctrines laid down by binding precedent.

The doctrine of stare decisis is a foundational pillar of the Indian judicial system. It ensures uniformity, consistency, and coherence in the development of legal principles. A consistent body of judicial precedent reinforces public confidence in the justice-delivery system and preserves the rule of law.

Accordingly, the Supreme Court has emphasized that there must be consistency in the annunciation of legal principles in its decisions, and that judicial discipline demands faithful adherence to binding precedent. Any deviation not only disrupts the harmony of legal doctrine but also undermines the credibility of the institution and the certainty expected by litigants and the public at large.

It is a settled principle of law that a decision rendered by a co-ordinate Bench is binding on subsequent Benches of equal or lesser strength. No Bench of the same strength can overrule or disregard a co-ordinate Bench decision; at best, it may refer the matter to a larger Bench if it disagrees.

Thus, any decision rendered in ignorance of a prior binding judgment of the same Court, or of a Court of coordinate or higher jurisdiction, or in ignorance of a statutory provision or a rule having the force of law, is classified as per incuriam. A per incuriam ruling carries no precedential authority. Such a decision cannot be regarded as laying down “good law,” even if it has not been expressly overruled.

A decision rendered per incuriam loses all precedential value. Such a ruling is not binding as a judicial precedent. All the authorities are fully entitled to disagree with and decline to follow a per incuriam decision, and a larger Bench can expressly overrule it.

ACTION PROVIDED AGAINST JUDGES REFUSING TO FOLLOW THE BINDING PRECEDENTS

The law is unequivocally settled by larger Benches of the Supreme Court, including several Constitution Benches, that Judges who neglect, omit, or refuse to apply the law and ratio laid down by the Supreme Court betray the constitutional trust reposed in them by the nation. Every Judge is duty-bound to consider the binding precedents relied upon by the parties, identify and examine the ratio decidendi, and—if inclined to take a different view—assign cogent, reasoned, and intelligible grounds for non-acceptance.

Mechanical or “rubber-stamp” reasons, superficial observations, pretence of consideration, or pretence of reasons or mere name-sake reference to binding precedents—followed by a contrary view based on minor, artificial, or irrelevant factual distinctions—do not satisfy this constitutional obligation. Such conduct has been expressly held to constitute judicial adventurism, perversity, dishonesty, and even contempt of the Supreme Court.

It is also firmly settled that when a Judge proposes to rely upon any judgment, ratio, or legal proposition suo motu—that is, not cited by the parties—the Court is constitutionally and procedurally bound to give the parties and their advocates a fair opportunity to address, explain, or rebut the said legal position.

Failure to afford such an opportunity renders the decision vitiated, being in violation of the principles of natural justice, including the fundamental rule of audi alteram partem.

Such an order becomes liable to be recalled, reviewed, or set aside, as reliance on an uncited or undisclosed authority without hearing the parties constitutes a denial of fair hearing and an abuse of judicial process.

Where this mandatory procedure is not followed, the Judge’s deliberate disregard of binding precedent amounts to a breach of the judicial oath, a violation of Articles 141 and 144 of the Constitution, and a serious disservice to the judicial institution and to the litigants for whose benefit the system exists. Such conduct brings disrepute upon the entire judiciary and strikes at the very foundation of the administration of justice.

The Supreme Court has repeatedly emphasized that judicial authority is not a personal prerogative but a constitutional trust, to be exercised strictly within the framework of Articles 141 and 144 of the Constitution, which mandate every court and every authority to act in conformity with the law declared by the Supreme Court and to aid its enforcement.

It is firmly settled that Judges who pass orders contrary to binding precedents are liable for both contempt proceedings and departmental disciplinary action. Judges are bound to apply the correct law and must not pass orders contrary to binding precedents even if such precedents are not cited by the parties.

A Judge who passes an order in disregard of even general guidelines issued by the Supreme Court is equally guilty of contempt. A Judge cannot take the defence that he or she was unaware of binding precedents or directions of the Supreme Court; ignorance of the law is no defence even for a judicial officer.

Such conduct has been judicially characterized as:

· “judicial adventurism”

· “acting with corrupt motive”

· “legal malice”

· “perversity”

· “judicial dishonesty”

· “fraud on power”

· “misuse of discretion”

Departmental actions—including suspension, dismissal, and compulsory retirement—have been repeatedly upheld on this ground, with courts observing that a Judge’s poor understanding of law or improper conduct has a “rippling effect” on the entire judicial system and gravely harms litigants.

In numerous cases, criminal prosecution has been directed against Judges who have misused judicial power to confer illegal benefits upon undeserving individuals through corrupt or improper means. The Indian Penal Code contains specific penal provisions applicable to dishonest or corrupt Judges who wilfully defy the mandates of law and pass unlawful, mala fide, or jurisdictionally perverse orders.

Importantly, criminal proceedings against a Judge are maintainable even if the judicial order itself is not challenged, since criminal liability for an unlawful act and appellate review of a judicial order are two separate and independent legal remedies. One deals with reversing the decision — the other with punishing the misconduct behind it. Both can coexist without limitation.

Where a Judge knowingly passes an order contrary to law, in breach of precedent, or by abusing judicial authority, multiple penal provisions stand attracted.

The applicable offences under the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) include:

Sections 198, 201, 228, 256, 257, 258, 336(2), 337, 316(5), 356(2) & (3), 352 BNS

Corresponding to (and replacing) the following earlier IPC offences:

Sections 166, 167, 192, 193, 218, 219, 220, 465, 466, 409, 500, 501, 504, 120B, 34, 109 IPC

Further, any misuse or abuse of judicial authority to extend an “undue favour” to an accused or any other person squarely invites Section 7A of the Prevention of Corruption (Amendment) Act, 2018, which penalizes any person who obtains or attempts to obtain an “undue advantage” for themselves or for another, through corrupt or illegal means, or by using personal influence to improperly influence the performance of a public servant’s official duty. The statutory punishment is imprisonment for not less than three years, extendable up to seven years, along with a fine.

(i) Ratilal Parmar v. State of Gujarat, 2024 SCC OnLine SC 298,

(ii) Rohan Vijay Nahar Vs. State 2025 SCC OnLine SC 2366,

(iii) State Bank of Travancore v. Mathew K.C., (2018) 3 SCC 85 ;

(iv) Harish Arora vs The Dy. Registrar 2025 SCC On Line Bom 2853;

(v) Union of India v. K.S. Subramanian, (1976) 3 SCC 677

(vi) Pradip J. Mehta v. CIT, (2008) 14 SCC 283

(vii) Dattani and Co. v. Income Tax Officer, 2013 SCC OnLine Guj 8841

(viii) Yogesh Waman Athavale v. Vikram Abasaheb Jadhav, 2020 SCC OnLine Bom 3443

(ix) Official Liquidator Vs. Dayanand (2008) 10 SCC 1

(x) U.P. Education for All Project Board v. Saroj Maurya, (2024) 12 SCC 609

(xi) Neeharika Infrastructure (P) Ltd. v. State of Maharashtra, (2021) 19 SCC 401

(xii) Emkay Exports, Mumbai v. Madhusudan Shrikrishna, 2008 SCC OnLine Bom 598

(xiii) Bank of Rajasthan Ltd. v. Shyam Sunder Tap Aria, 2006 SCC OnLine Bom 755

(xiv) R.R. Parekh Vs. High Court of Gujrat (2016) 14 SCC 1,

(xv) Vijay Shekhar v. Union of India, (2004) 4 SCC 666,

(xvi) Umesh Chandra Vs State of Uttar Pradesh & Ors. 2006 (5) AWC 4519 ALL;

(xvii) K. Veeraswami Vs. Union of India (1991) 3 SCC 655 (Five-J);

(xviii) Raman Lal Vs. State 2001 Cri. L. J. 800;

(xix) Re: C. S. Karnan (2017) 7 SCC 1;

(xx) Govind Mehta Vs. State of Bihar (1971) 3 SCC 329,

(xxi) Mohd. Nazer M.P. v. State (UT of Lakshadweep), 2022 SCC OnLine Ker 7434,

(xxii) Jagat Jagdishchandra Patel Vs. State of Gujrat 2016 SCC OnLine Guj 4517;

(xxiii) K. Rama Reddy Vs State 1998 (3) ALD 305,

On reasoned order :-

(i) Neeharika Infrastructure Pvt. Ltd. v. State of Maharashtra, 2021 SCC OnLine SC 315;

(ii) Vishal Ashwin Patel v. CIT, (2022) 14 SCC 817;

(iii) Shailesh Bhansali v. Alok Dhir, 2025 SCC OnLine SC 512;

(iv) Hakim Nazir Ahmad v. Commissioner, 2025 SCC OnLine J&K ___,

(v) Johra v. State of Haryan a, (2019) 2 SCC 324;

(vi) U.P. Education for All Project Board v. Saroj Maurya, (2024) 12 SCC 609;

(vii) P. Radhakrishnan & Anr. v. Cochin Devaswom Board & Ors., 2025 INSC 1183;

(viii) Delta Foundations v. KSCC Ltd., (2003) 4 ICC 251 (Ker) (DB)

Supporters of Justice A.S. Oka have described the recent judicial development as an act of “revenge” by CJI Bhushan Gavai, citing Justice Oka’s recent interview in which he openly criticised the CJI for elevating his own nephew as a High Court Judge, calling it a direct conflict of interest.

However, legal experts associated with the Indian Bar Association have firmly rejected this narrative. They state that the ruling delivered by CJI Gavai is legally correct, constitutionally sound, and fully consistent with binding Constitution Bench precedents. According to them, concerns regarding Justice Oka’s judicial conduct long predate the current controversy.

They note that despite Justice Oka portraying himself as a champion of transparency, his judicial record has been marred by serious allegations — including passing orders contrary to binding Supreme Court precedents, encouraging corruption, and promoting dishonest or frivolous litigation during his tenure at the Bombay High Court.

Serious concerns had earlier arisen in cases involving the Anna Hazare matter, Section 340 CrPC perjury proceedings, and other matters.

Members of the Indian Bar Association have stated that they now intend to initiate appropriate criminal proceedings against Justice Abhay Oka for alleged fraud, judicial dishonesty, and promoting corrupt litigation practices, strictly in accordance with law and binding Supreme Court jurisprudence.