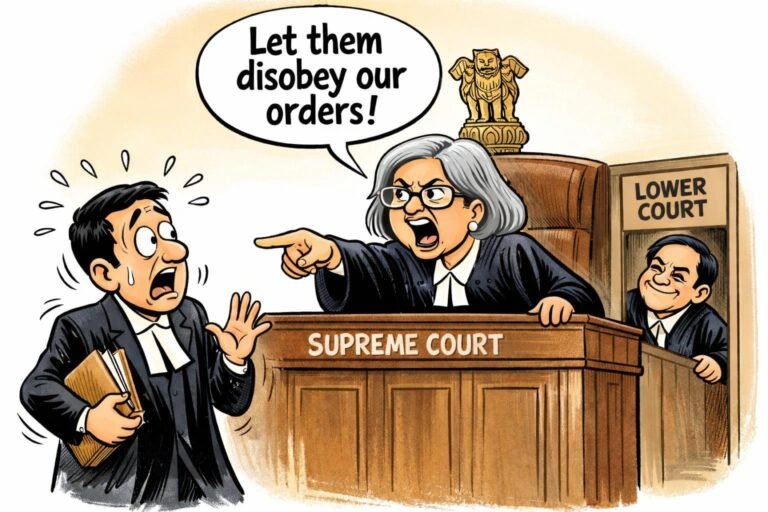

[Big Breaking] Supreme Court Condemns Wrongful Criminal Contempt Conviction by Bombay High Court; Warns Against Misuse of Contempt to Silence Criticism. (Vineeta Srinandan v. High Court of Judicature at Bombay, 2025 INSC 1408).

In the impugned judgment, the Bombay High Court, through a Division Bench presided over by Justice G. S. Kulkarni, relied upon the overruled decision in C. K. Daphtary v. O.P. Gupta to convict and sentence a woman for criminal contempt. Supreme Court has categorically condemned the recording of a criminal contempt conviction by the Bombay High Court on the basis of irrelevant, inapplicable, and obsolete precedents, and has expressly cautioned that the contempt jurisdiction cannot be misused as a tool to silence criticism.

In light of repeated instances where overruled judgments and non-binding precedents have been mechanically invoked in contempt matters, the Indian Bar Association has decided to publish an authoritative book compiling overruled precedents and binding constitutional law governing contempt of court. The objective of this publication is to prevent recurring violations of citizens’ fundamental rights, ensure judicial accountability, and promote strict adherence to Article 141 of the Constitution, so that contempt jurisdiction is exercised strictly within its constitutional limits.

It is settled law that a High Court Judge who passes orders in conscious disregard of binding precedents of the Hon’ble Supreme Court, or who relies upon overruled judgments, renders himself liable for civil contempt under Sections 2(b), 12, and 16 of the Contempt of Courts Act, 1971, for willful disobedience of law declared under Article 141 of the Constitution and any citizen can file contempt petition against the said Judge. [Prominent Hotels v. New Delhi Municipal Corporation, 2015 SCC OnLine Del 11910; In Re: M.P. Dwivedi, (1996) 4 SCC 152; Re: C. S. Karnan (2017) 7 SCC 1 ] It is further evident on the face of the record that, in the impugned judgment, the Bombay High Court, through a Bench presided over by Justice G. S. Kulkarni, relied upon the decision in C. K. Daphtary v. O.P. Gupta to convict and sentence a woman for criminal contempt, despite the said judgment having been rendered inapplicable and effectively overruled by subsequent binding decisions of the Hon’ble Supreme Court, including Constitution Bench jurisprudence and statutory developments post the Contempt of Courts (Amendment) Act, 2006. Reliance upon such an obsolete authority ipso facto renders the conviction unlawful and unsustainable.

The Hon’ble Supreme Court has, on earlier occasions as well, expressly cautioned against mechanical and misplaced reliance on unrelated precedents in contempt matters. In Mehmood Pracha v. Central Administrative Tribunal, 2022 SCC OnLine SC 1029, the Hon’ble Supreme Court set aside the conviction of Advocate Mehmood Pracha, holding that the decision in Leila David (3) v. State of Maharashtra, (2009) 10 SCC 348— which pertained to the act of throwing footwear in court— could not be applied to cases involving allegedly inappropriate or forceful arguments advanced by advocates. The Court underscored that context, facts, and ratio decidendi are determinative, and contempt law cannot be applied by analogy or exaggeration or relying upon irrelevant judgments.

It is further pertinent to note that a separate and independent petition seeking prosecution of Justice G. S. Kulkarni for misuse of criminal contempt jurisdiction, alleged fabrication of judicial record, reliance on overruled judgments, and willful disregard of binding precedents, resulting in the false implication of an advocate in a frivolous charge of criminal contempt, has already been filed by Advocate Vijay Kurle. The said petition is founded on cogent, documentary, and legal evidence and is presently pending adjudication before the Bombay High Court’s Bench of Justice A. S. Gadkari.

The pendency of the aforesaid proceedings clearly demonstrates that the issues raised herein are neither academic, hypothetical, nor speculative, but instead form part of an ongoing process of judicial scrutiny concerning the alleged abuse and misuse of contempt powers, and raise questions of grave constitutional and institutional significance.

The Supreme Court has unequivocally deprecated the judgment dated 23 April 2025 passed in Suo Motu Criminal Contempt Petition No. 02 of 2025, wherein the High Court recorded a conviction for criminal contempt by wrongly and mechanically relying upon irrelevant and inapplicable precedents relating to “scandalization of the court,” without undertaking any analysis of the precise ratio decidendi, the factual matrix, or the subsequent constitutional and statutory developments governing the field of contempt law.

The Apex Court has repeatedly cautioned that contempt jurisdiction, being quasi-criminal, cannot be exercised casually and must be exercised with due care and circumspection. It is equally well settled that a judge acting in violation of clear statutory provisions and binding precedents is not entitled to claim the defence of “good faith” or “ignorance of law.” Section 2(11) of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, read with Section 52 of the Indian Penal Code, mandates that good faith requires due care, caution, and fidelity to law; deliberate or reckless disregard of settled law negates any claim of bona fides. The Supreme Court, in R.R. Parekh v. High Court of Gujarat, (2016) 14 SCC 1, held as under that acting contrary to law in the discharge of judicial functions constitutes serious misconduct, and it legitimately leads to the inference that the judge was actuated by extraneous or corrupt considerations. No further proof is required for taking action against such a judge. On such findings, the concerned judges were dismissed from service.

Personal Liability of Delinquent Judges and Right of Victim to Constitutional Compensation

It is further settled in law that delinquent judges are not immune from civil consequences, and may be held personally liable to compensate a victim whose fundamental rights have been violated by patently unlawful judicial orders. Where a court order results in illegal deprivation of liberty, dignity, or reputation, in violation of Articles 14, 19, and 21 of the Constitution, the victim is entitled to public law compensation.

The law is equally settled that such compensation is to be awarded in the first instance against the State in writ jurisdiction, and the State is thereafter entitled to recover the amount from the concerned judges responsible for the violation, upon due determination. The victim of the unlawful judicial action in the present case is the said lady, who has suffered grave constitutional injury, and is therefore entitled to compensation under Article 226/32 of the Constitution.

This legal position stands firmly established by a long line of binding precedents, including: Walmik Bobde v. State of Maharashtra, 2001 ALL MR (Cri) 1731; Ramesh Lawrence Maharaj vs Attorney General of Trinidad and Tobago (1978) 2 WLR 902, McLeod v. St. Aubyn, (1899) AC 549; Luis Hens Serena v. Spain, 2008 SCC OnLine HRC 20; Directions in the Matter of Demolition of Structures, In Re, (2025) 5 SCC 1; Lucknow Development Authority v. M.K. Gupta, AIR 1994 SC 787.

These authorities unequivocally affirm that constitutional courts are duty-bound to grant monetary compensation as a public law remedy for abuse of power and violation of fundamental rights, and that judicial office does not confer immunity from accountability when actions are ultra vires, arbitrary, or mala fide.

Gross Illegality of the Impugned Judgment Dated 23.04.2025 — Four Foundational Jurisdictional Defects

The impugned judgment dated 23 April 2025, passed by the Division Bench of the Bombay High Court presided over by Justice G. S. Kulkarni and Justice Advait Sethna, is vitiated by fundamental illegality and lack of jurisdiction, inter alia, for the following compelling reasons:

Firstly, as per the Bombay High Court Rules and the law laid down by the Hon’ble Supreme Court in Bal Thackeray v. Harish Pimpalkhute, (2005) 1 SCC 254, only the Chief Justice of the High Court is competent to take suo motu cognizance of criminal contempt where the alleged contempt arises out of a publication made outside the court. The Bench presided over by Justice G. S. Kulkarni had no authority in law to take suo motu cognizance of such alleged contempt. Consequently, the cognizance itself, and all proceedings flowing therefrom, including trial, conviction, and sentence, are void ab initio.

Secondly, it is settled law that a judge who initiates contempt proceedings or takes cognizance of alleged contempt committed in facie curiae is disqualified from adjudicating the matter on merits. Such judge is under a mandatory duty to inform the alleged contemnor of her right to be tried by another judge or an independent Bench. Failure to do so vitiates the proceedings on grounds of bias, denial of natural justice, and violation of Article 21.

This principle stands conclusively settled by binding authorities, including:

[ Mohd. Zahir Khan Vs. Vijai Singh AIR 1992 SC 642, Suo Motu (Court on it own Motion Vs. Satish Mahadeorao Uke 2019 SCC OnLine Bom 5164, Court own its own motion Vs. Nilesh C. Ojha 2019 SCC OnLine Bom 3908, R. Vs. Commissioner of Pawing (1941) 1 QB 467, R .V. Lee, (1882) 9 Q.B.D. 394, Mitchell v. State 320 Md. 756 (Md. 1990), Allinson Vs. General Council of Medical Education and Registration, (1894) 1 QB 750 at p. 758)]

Thirdly, the Ld. Judge wholly failed to adhere to the self-imposed restraint and the six well-settled prohibitory guidelines laid down by the Hon’ble Supreme Court governing the exercise of contempt jurisdiction, as authoritatively enunciated in In Re: S. Mulgaonkar, (1978) 3 SCC 339, and reiterated in T.C. Gupta v. Hari Om Prakash, (2013) 10 SCC 658.

The Hon’ble Supreme Court ruled as under that contempt jurisdiction must be invoked only when silence is not an option, and that courts must avoid hypersensitivity, irritability, and overreaction, even in the face of outspoken or harsh criticism. The Court categorically held that contempt power is not meant to silence dissent or criticism but to protect the administration of justice in exceptional circumstances.

In In Re: S. Mulgaonkar, (1978) 3 SCC 339, the Hon’ble Supreme Court, while laying down the mandatory principles of restraint governing the exercise of contempt jurisdiction, illustrated the doctrine through the metaphor of an elephant’s steady march undeterred by a dog’s barking, and observed as under:

“The Court is willing to ignore, by a majestic liberalism, trifling and venial offences — the dogs may bark, the caravan will pass. The Court will not be prompted to act as a result of an easy irritability. Much rather, it shall take a noetic look at the conspectus of features and be guided by a constellation of constitutional and other considerations when it chooses to use, or desist from using, its power of contempt.”

In the present case, none of the threshold conditions warranting invocation of contempt jurisdiction were satisfied.

Fourthly, Justice G. S. Kulkarni relied upon overruled and obsolete judgments, including C. K. Daphtary v. O.P. Gupta, (1971) 1 SCC 626, and D.C. Saxena v. Chief Justice of India, (1996) 5 SCC 216, to hold that justification or truth is not a permissible defence in contempt, thereby implying that even a true publication would constitute punishable contempt. Such a proposition is manifestly erroneous, unconstitutional, and unsustainable in law.

The finding in C. K. Daphtary was itself per incuriam, as it directly conflicted with the earlier Constitution Bench judgment in Bathina Ramakrishna Reddy v. State of Madras, AIR 1952 SC 149, wherein the Hon’ble Supreme Court clearly ruled that exposure of corrupt practices of a judge, when based on proof is not a contempt but it is in the public interest.

Furthermore, the decision in C. K. Daphtary stands expressly rendered statutorily overruled and inapplicable by the Hon’ble Supreme Court in:

• Biman Basu v. Kallol Guha Thakurta, (2010) 8 SCC 673, para 23

• P.N. Duda v. P. Shiv Shankar, (1988) 3 SCC 167, para 39

More importantly, pursuant to the Contempt of Courts (Amendment) Act, 2006, truth and justification were statutorily recognized as valid and complete defences to a charge of contempt, provided the disclosure is bona fide and in public interest. This statutory mandate has been conclusively affirmed by Constitution Bench judgments, including Subramanian Swamy v. Arun Shourie, (2014) 12 SCC 344, wherein it was settled that no cognizance of criminal contempt can be taken if the publication is true or does not appear to be false, even if it allegedly lowers the public image of a judge.

Fifthly — Reliance on Judgments Without Granting Opportunity of Hearing (Violation of Natural Justice)

Fifthly, Justice G. S. Kulkarni relied upon several judgments suo motu, without affording the affected party any opportunity to make submissions to demonstrate that such judgments were overruled, inapplicable, or distinguishable. This practice is squarely violative of the principles of natural justice.

The Hon’ble Supreme Court has strongly deprecated this very practice in P. Radhakrishnan v. Cochin Devaswom Board, 2025 INSC 1183, holding that reliance on authorities without notice or opportunity to address them vitiates the adjudicatory process and renders the decision procedurally unfair and unconstitutional.

Sixthly — Illegal Trial Procedure: Judge Acting as Prosecutor and Adjudicator

Sixthly, the entire trial is vitiated as the contempt proceedings were not conducted by the State through its law officers, but were effectively prosecuted and adjudicated by the Judge himself, which is impermissible in law.

Criminal contempt is a criminal offence, and the alleged contemnor is entitled to all constitutional and procedural safeguards available to an accused in a criminal trial, including:

1. Prosecution by the State through a public prosecutor,

2. Adjudication by a neutral and independent judge, and

3. Separation between the roles of complainant, prosecutor, and judge.

The Bombay High Court Rules mandate impleadment of the State as a respondent and prosecution through State law officers. The Judge who takes cognizance cannot act as prosecutor, nor can he try the case himself.

This principle stands affirmed by binding authorities, including:

• P. Mohanraj v. Shah Bros. Ispat (P) Ltd., (2021) 6 SCC 258

• Robertson v. United States, 560 U.S. 272 (2010)

• Suo Motu Vs. S.B. Vakil, Advocate, High Court of Gujarat and Ors. 2006 SCC OnLine Guj 102,

• Young v. United States ex rel. Vuitton et Fils S.A., 481 U.S. 787 (1987)

The underlying case before the Bombay High Court arose from the publication of a circular issued by Smt. Vineeta Srinandan, wherein allegations were made accusing certain elements of the judiciary of being part of a so-called “Dog Mafia.” Justice Kulkarni took suo motu cognizance of the publication and registered the matter as SMCP (Criminal) No. 2 of 2025, sentencing Smt. Srinandan to one week’s imprisonment, notwithstanding her expression of remorse and tendering of an unconditional apology.

The Supreme Court’s intervention in the matter reinforces settled constitutional principles that contempt jurisdiction is corrective, not punitive, and that courts must exercise extreme restraint, particularly where freedom of speech, fair criticism, and statutory defences expressly recognized by Parliament are involved.