Justice Nagarathna’s Appeal Against Overruling Judgments Draws Heavy Criticism.

Legal Community and Indian Bar Association Say: “Confusing, Misdirected, and Contrary to the Basic Constitutional Doctrine That Wrong Law Cannot Be Allowed to Live”

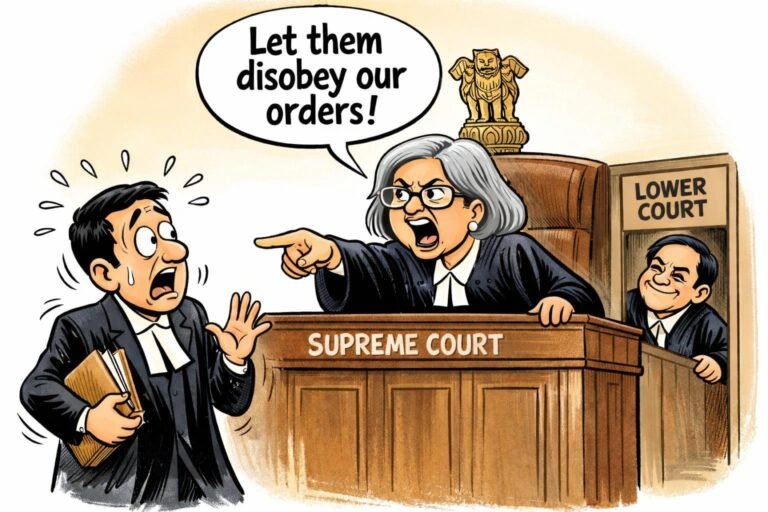

Justice B.V. Nagarathna’s recent public remarks—that judicial decisions should generally not be overruled by later Benches, especially after the retirement of the judges who authored them—have sparked strong and widespread criticism from senior advocates, constitutional scholars, and the Indian Bar Association.

Speaking at an event, Justice Nagarathna stated that the legal fraternity must respect judgments “for what they are” and should not discard them merely because “faces have changed,” adding that judgments are “not written in sand but in ink.”

These remarks have been widely interpreted as an indirect criticism of the recent three Judge Bench judgment in VANASHAKTI v. Union of India, 2025 INSC 1326, authored by former Chief Justice Bhushan Gavai.

In that landmark ruling, the three Judge Bench expressly overruled a two-judge bench judgment delivered by Justice Abhay Oka (now retired), which had been widely condemned by jurists as grossly illegal, manifestly erroneous, and ex facie per incuriam. Justice Nagarathna’s comments—suggesting that later Benches should refrain from revisiting or overruling earlier decisions after the authors have retired—are therefore being seen as an indirect rebuke to the VANASHAKTI ruling, despite the fact that the three Judge Bench only fulfilled its constitutional duty to correct an erroneous precedent that could not be allowed to survive.

Legal Community Says: Her Statement Is Contrary to Precedent and Constitutional Doctrine

Members of the bar have pointed out that Justice Nagarathna’s view is not in harmony with the established principles governing judicial precedent, and is contrary to the very structure of constitutional adjudication.

Her statement has been labelled “confusing, misdirected, and constitutionally unsound,” because it appears to suggest that:

Incorrect or per incuriam judgments should remain untouched,

Larger Benches should refrain from correcting earlier judicial errors, and

Judicial mistakes should survive merely because of the retirement of previous judges.

Constitution Bench Law Says the Opposite — Errors MUST Be Corrected

The critics rely on several binding Constitution Bench judgments, the most prominent being Distributors (Baroda) (P) Ltd. v. Union of India, (1986) 1 SCC 43, where the Supreme Court famously held:

“To perpetuate an error is no heroism. To rectify it is the compulsion of judicial conscience.”

Legal experts further point out that Justice Nagarathna is undoubtedly aware of the landmark Constitution Bench and coordinate Bench rulings which expressly reject the very proposition she advanced. In State of M.P. v. Narmada Bachao Andolan, (2011) 7 SCC 639, a three Judge Bench of the Supreme Court made the principle unmistakably clear: courts are duty-bound to correct errors, not perpetuate them.

It is ruled as under;

“69. The courts are not to perpetuate an illegality, rather it is the duty of the courts to rectify mistakes. While dealing with a similar issue, this Court in Hotel Balaji v. State of A.P. [1993 Supp (4) SCC 536 : AIR 1993 SC 1048] observed as under : (SCC p. 551, para 12)

“12. … ‘2. … To perpetuate an error is no heroism. To rectify it is the compulsion of judicial conscience. In this we derive comfort and strength from the wise and inspiring words of Justice Bronson in Pierce v. Delameter [1 NY 3 (1847)] , AMY at p. 18:

“a Judge ought to be wise enough to know that he is fallible and therefore ever ready to learn : great and honest enough to discard all mere pride of opinion and follow truth wherever it may lead : and courageous enough to acknowledge his errors.”’ [Ed. : As observed in Distributors (Baroda) (P) Ltd. v. Union of India, (1986) 1 SCC 43, p. 46, para 2.] ”

- In Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, In re [(1995) 3 SCC 619] this Court observed : (SCC p. 629, para 10)

“10. … None is free from errors, and the judiciary does not claim infallibility. It is truly said that a judge who has not committed a mistake is yet to be born. Our legal system in fact acknowledges the fallibility of the courts and provides for both internal and external checks to correct the errors. The law, the jurisprudence and the precedents, the open public hearings, reasoned judgments, appeals, revisions, references and reviews constitute the internal checks while objective critiques, debates and discussions of judgments outside the courts, and legislative correctives provide the external checks. Together, they go a long way to ensure judicial accountability. The law thus provides procedure to correct judicial errors.””

These binding precedents leave no room for any doctrine that forbids overruling; rather, they mandate that incorrect judgments must be set aside in the interest of justice, constitutional fidelity, and public confidence. It is on this solid foundation that the criticism of Justice Nagarathna’s remarks has arisen—because the Supreme Court itself has repeatedly held that the vitality of the judicial process lies not in preserving errors, but in courageously correcting them.

Building on these foundational principles, critics point out that the Supreme Court has repeatedly emphasised that judicial discipline does not mean blindly upholding past errors, but rather ensuring that the law evolves correctly, coherently, and constitutionally. Numerous Constitution Bench judgments—including Keshav Mills Co. Ltd. v. CIT, Bengal Immunity Co., Waman Rao, and Central Board of Dawoodi Bohra Community—affirm that a precedent that is incorrect, per incuriam, or in conflict with larger bench authority cannot be permitted to survive merely for the sake of stability. The Court has clarified that stare decisis is a guiding principle, not an iron cage, and must yield whenever adherence to a past ruling would result in injustice, doctrinal confusion, or violation of constitutional norms. Therefore, legal scholars argue that Justice Nagarathna’s suggestion contradicts the Supreme Court’s settled position that the judiciary must actively correct its mistakes, and that judicial conscience, not judicial sentiment, must guide precedential review. Overruling Wrong Judgments Is a Constitutional Duty

Legal experts therefore argue that Justice Nagarathna’s appeal—suggesting that judgments should not be “tossed out” by subsequent Benches—runs counter to the foundational constitutional requirement that courts must uphold correctness over continuity.

They emphasize that:

Wrong decisions cannot be allowed to remain as living law,

Per incuriam or erroneous judgments must be struck down, and

Judicial conscience demands correction, not preservation, of mistakes.

Accordingly, the legal fraternity asserts that the constitutional scheme requires courts to discard erroneous precedent, rather than allow it to continue merely as a matter of sentiment or seniority.