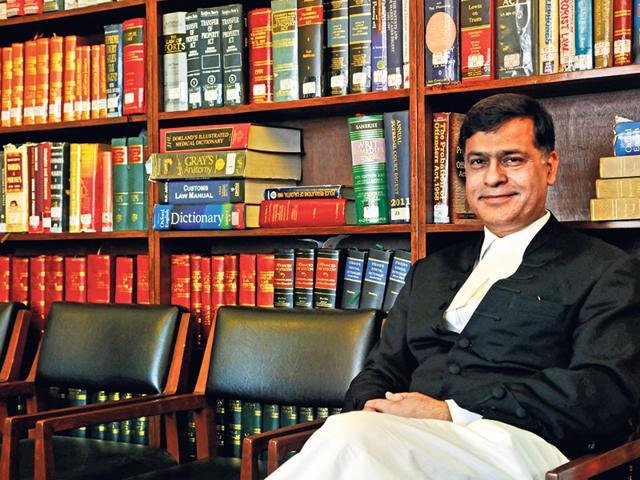

Gross Professional Misconduct:- A complaint has been filed against Senior Advocate Siddharth Luthra for misleading the Delhi High Court by relying on overruled judgments in an attempt to secure the conviction of various advocates practicing at the Tis Hazari Courts.

The Indian Lawyers and Human Rights Activists Association, which filed the complaint, has also produced documentary evidence alleging additional criminal offences, including perjury and fraud upon the Court committed by Adv. Luthra.

The complaint seeks permanent removal of his name from the advocates’ roll, withdrawl of senior counsel designation by citing this as a grave act of professional misconduct and abuse of the court’s trust.

Many lawyers supported the complaint and sought stern and quick action.

The complaint categorically asserts—supported by documentary evidence—that Senior Advocate Siddharth Luthra, while acting as amicus curiae in Contempt Proceedings Against Tis Hazari Lawyers, In re, (2023) 4 HCC (Del) 100, relied upon per incuriam and overruled judgments, including Pritam Pal v. High Court of Madhya Pradesh, 1992 (1) SCALE 416, Re: Vijay Kurle, (2020) 13 SCC 616, and Prashant Bhushan, In re, (2021) 3 SCC 160.

The complaint states that Mr. Luthra deliberately suppressed the fact that Re: Vijay Kurle and Prashant Bhushan are themselves under challenge before a larger Bench, and that the writ petitions questioning those judgments have already been admitted. Indeed, when those writ petitions were first listed, Mr. Luthra appeared and requested that he continue as amicus. The Supreme Court declined to continue him and he was discontinued with disgrace. [Prashant Bhushan v. Union of India, 2022 SCC OnLine SC 2222]

The Delhi High Court, in its recent judgment Renew Wind Energy (AP2) Pvt. Ltd. v. Solar Energy Corporation of India, 2025 SCC OnLine Del 8252, has articulated firm and unequivocal principles on the advocate’s duty of candour towards the Court. The Court held that reliance on judgments that are overruled, stayed, or under challenge—without disclosing their true legal status—constitutes gross professional misconduct.

It emphasized that every advocate is duty-bound to make a full, fair, and accurate disclosure regarding the precedential value of any decision cited. Any lawyer or law firm that relies upon overruled, reviewed, or pending-appeal judgments without candid disclosure commits a serious breach of professional ethics and violates the duty of candour owed to the Court.

The Court further warned that deliberate suppression or misrepresentation of the status of a precedent strikes at the very foundation of the justice-delivery system and will invite strict consequences. The functioning of the judicial process, the Court noted, is built upon mutual trust between the Bar and the Bench, and every stakeholder—litigant, counsel, and Court—bears a collective responsibility to preserve this institutional integrity. Any lapse weakens public confidence in the system as a whole.

Further, the two judgments relied upon by him (Re: Vijay Kurle and Prashant Bhushan) are founded entirely on overruled precedents, namely Pritam Pal and C.K. Daphtary v. O.P. Gupta, (1971) 1 SCC 626.

Pritam Pal was expressly overruled in Bal Thackeray v. Pimpalkhute, (2005) 1 SCC 254. C.K. Daphtary was declared statutorily overruled and non-binding in P.N. Duda v. P. Shiv Shanker, (1988) 3 SCC 167, and Biman Basu v. Kallol Guha Thakurta, (2010) 8 SCC 673.

Additionally, Mr. Luthra withheld binding Constitution Bench rulings in Subramanian Swamy v. Arun Shourie, (2014) 12 SCC 344 and Re: Justice C.S. Karnan, (2017) 7 SCC 1, which overrules the ratio laid down in the C. K. Daphtary’s case. The law is very well settled by the larger Benches that truth is a valid defence and that bona fide exposure of judicial misconduct is protected speech and a constitutional duty under Article 51-A.

It is further noted that C.K. Daphtary is per incuriam, having been delivered in ignorance of binding Constitution Bench precedent in Bathina Ramakrishna Reddy, AIR 1952 SC 149. This flaw was highlighted in an article authored by former Solicitor General T.R. Andhyarujina in (2003) 4 SCC (Jour) 12.

The complaint also refers to In Re: Special Reference No. 1 of 1964, where a Seven-Judge Bench made the Privy Council judgment in Ambard v. Attorney-General of Trinidad (1936 PC) binding to all Judges in India. The principle established is that no person can be convicted of contempt unless the allegations against judges are proved to be false. C.K. Daphtary failed to consider this binding law, therefore it is per incuriam and non binding. These issues form part of the pleadings in the pending writ petitions challenging Re: Vijay Kurle. In W.P. (Crl.) No. 244/2020, the specific prayer is:

“Direct all authorities in the country not to follow the law and ratio laid down in the judgments dated 27.04.2020 and 04.05.2020 passed in Re: Vijay Kurle & Ors., SMCP (Cri) No. 02/2019.”

Despite this, Mr. Luthra placed reliance on the judgments of Pritam Pal v. High Court of Madhya Pradesh, 1992 (1) SCALE 416, Re: Vijay Kurle, (2020) 13 SCC 616, and Prashant Bhushan, In re, (2021) 3 SCC 160, by suppressing that they are under challenge and writ is admitted. He mislead the High Court and argued by suppressing binding law, ignoring pending writs, and relying on overruled judgments.

The complaint cites Sajid Khan Moyal v. State of Rajasthan, 2014 SCC OnLine Raj 1450, where the High Court held that citing an overruled judgment is criminal contempt on the part of the advocate.

It further relies on R. Muthukrishnan v. High Court of Madras, (2019) 16 SCC 407, where the Supreme Court held that advocates must rely only on binding precedents, must not twist facts or suppress law, and must uphold the highest ethical standards. Misconduct that damages the justice system renders an advocate “deadwood”—unfit to remain in the profession—and liable to removal from the rolls.

It is a well-established principle of professional ethics, as consistently reiterated by the Hon’ble Supreme Court of India, that an advocate—and more particularly, a Senior Advocate—owes a paramount duty of candour, fairness, and complete disclosure to the Court. An advocate is legally and ethically bound to bring to the Court’s attention all relevant facts and precedents, including those that may be adverse to the client’s case or favourable to the opposing party. Suppression or deliberate withholding of such material, including binding judgments, constitutes a fraud upon the Court and amounts to gross professional misconduct, inviting disciplinary as well as penal consequences under the Advocates Act, 1961, the Bar Council of India Rules, and settled judicial pronouncements.

Supreme Court has clearly ruled that State of Orissa v. Nalinikanta Muduli, (2004) 7 SCC 19, s E.S. Reddi , T.V. Choudhary, In re, (1987) 3 SCC 258; Sunita Pandey v. State of Uttarakhand, 2018 SCC OnLine Utt 933, R. Muthukrishnan v. High Court of Madras, (2019) 16 SCC 407 ; Lal Bahadur Gautam v. State of U.P., (2019) 6 SCC 441, R. Gangadharappa Vs. Kondla Nanjamma ILR 2016 KAR 3029, Hindustan Organic Chemicals Ltd. v. ICI India Ltd., 2017 SCC OnLine Born 74, Sajid Khan Moyal v. State of Rajasthan, 2014 SCC OnLine Raj 1450, Kusha Duruka v. State of Odisha, (2024) 4 SCC 432, Citing precedents where senior lawyers were stripped of their designation or barred from practice—such as R.K. Anand v. Delhi High Court, (2009) 8 SCC 106, and Yatin Oza v. High Court of Gujarat, (2021) SCC OnLine SC 1004—the Indian Lawyers and Human Rights Activists Association has called for:

Institution of disciplinary proceedings by the Bar Council of India and Bar Council of Maharashtra & Goa, with time-bound inquiry into the allegations of suppression, distortion, and professional deceit;

Permanent cancellation of Sanad (licence to practice) of Mr. Siddharth Luthra, under Section 35(3) of the Advocates Act;

Immediate withdrawal of their Senior Advocate designation by the Hon’ble Delhi High Court to protect the dignity of the institution;

Notification to all High Courts and the Supreme Court Registry to refrain from assigning him appearances in matters involving precedential integrity until inquiry is completed.